Maybe this is just on my mind because we’re in the middle of Chanukkah and feeling nostalgic about my childhood and because I’ve been starting new traditions with my own child, or maybe it’s just because I’m in the process of editing Home Ice Advantage. But there’s a particular American-Jewish experience growing up where your parents love to tell you every time you come across another Jewish person, whether that’s in movies, authors, or sports. As a child and a teen I had a keen eye out for Jewish hockey players, but at that time, they were few and far between. We had Mathieu Schneider and Mike Cammalleri and Eric Nyström and Jeff Halpern, and there wasn’t much else outside of them.

It’s been a real joy, within the last few years, to have so many more Jewish players in the league. Granted, it’s still a relatively small number comparatively, but to someone who grew up with maybe one or two guys at a time, to be able to watch three Jewish brothers (Quinn, Jack, and Luke Hughes) on the ice at the same time feels like a dream. It’s amazing to see those brothers get drafted in the top ten, or to see Quinn wearing a C for the Canucks. It’s incredible to watch Zach Hyman playing in Edmonton wearing #18. It’s satisfying to see Jason Zucker recognized for his charitable work with children’s hospitals. It makes my heart so fucking happy to see Devon Levi, a Jewish goalie and a huge Star Wars nerd, doing Qui-Gon Jinn’s meditation routine on the ice during TV timeouts.

But what I was interested in exploring for this post wasn’t just the modern day Jewish players, or even the Jewish players of my youth, but the really historical players. The ones who laid the foundation for everyone to come after. The really neat thing when I started to poke around in here is to see a few patterns: Jewish parents have always been Jewish parents, Jewish players have dealt with the same shit from the beginning, and Montreal is at the heart of all of it. A lot of these thoughts and feelings were echoed, unintentionally, when I was writing Home Ice Advantage and specifically, the character of Eric Aronson, a middle-aged retired player-turned-coach from Montreal.

We’ll look at them in roughly chronological order.

I’m also warning you that this is a long one—you probably won’t be able to read all of it in an email alone.

The first

Samuel Rothschild’s family were the first Jews to move to Sudbury, Ontario (fans of Letterkenny and Shoresy may have also had a moment of recognition here), and he was the first Jewish player in the NHL, too. There’s some debate over some of the other firsts (the goalie lineage specifically is tangled; and whether or not Gizzy Hart is Jewish is something we’ll have to get into) but everyone seems to agree: Sam Rothschild was the first.

He began his hockey career in Montreal, first for the Harmonia, then at McGill University, and later for the Montreal Stars, before returning to his hometown Sudbury Wolves.

At the time, there were two teams in Montreal, the Canadiens, who were the Francophone team and remain the Francophone team, and the Wanderers, who were the “Anglophone” team. After the Wanderers folded, the English-speaking fans no longer had a team of their own. At first, the NHL didn’t want to expand again, but when the new Anglophone team—the Maroons—could actually pay the fee, the league relented.

And that’s where Sam came in: in 1924, he signed with the Maroons for their inaugural season. That meant a $1,000 signing bonus, and a salary of $3,500 a year for a two-year contract.

At the time, he was also the first Jewish player in the NHL since its founding in 1919. I’ve read at least one article that implies the Maroons signed Sam because they were hoping to draw in fans from “the city’s English-speaking Jewish community,” which sounds plausible, but wasn’t a sourced claim.

I do keep coming back to, quite often in this, how relatively small the Jewish community in Canada was at that time and how much of it was and had been, from the beginning, concentrated in Montreal. How hockey itself was already ingrained in the culture of Canada, and how in some ways, entry into this league was belonging. It does feel plausible that the Maroons would have seen a Jewish player as a draw—I remember how proudly my own father would always say, “See him? He’s Jewish.”

He played his first game on December 1, 1924.

During his playing years, Sam was 5’ 6” and 145 lbs, a left winger. He won the Stanley Cup with the Maroons in the 1925-26 season, and he may be the first Jewish player with his name engraved on the Cup. (I wasn’t able to find an answer one way or another whether there was a Jewish player on any of the teams engraved on the Cup before the existence of the NHL—Gizzy Hart won it with the Cougars, the last non NHL team to win the Cup in 1923-24, but whether or not that Hart was Jewish or not seems to be a matter of debate.)

Sam’s last season in the NHL was 1927-28 with both the Pittsburgh Pirates and the New York Americans. I’ve seen him described as “a skilled forward with a nose for the net,” but looking at his stats on Hockey Reference, he played a hundred career games with eight goals and seven assists, so I’m not sure how accurate that statement really is (two of those goals, however, were game winners). His career ended that year with a knee injury.

After his retirement, he coached the junior Sudbury Wolves to the 1932 Memorial Cup Championship. In addition to hockey, he was really involved with curling (he’s in the Canadian Curling Hall of Fame) and served a few years on Sudbury’s city council.

Regardless of his actual impact on the league, this is unassailable: he was the first.

The first (coaches edition)

The Hart family is woven into Canadian history: Aaron Hart, born in 1724, is considered the father of Canadian Jewry. His descendant, Cecil “Cece” Mordecai Hart was always involved in hockey, whether it was playing or coaching or managing. Again, there are so many links to Montreal: Aaron Hart settled in Trois-Rivières, a small city about an hour and a half’s drive from Montreal and where the Habs’ current ECHL team is located.

Cece himself was born in Bedford, Quebec, and stayed in the greater Montreal area, working first with the Montreal Star Club, then the Montreal City Hockey League, and then the Eastern Canada Amateur Hockey Association. In 1923, Cece’s father, David, donated the Hart Trophy, awarded to the most valuable player every season, to the NHL. (The original trophy has since been retired, but the current version—the Hart Memorial Trophy—is named after Cece).

Cece served as the initial club director of the Habs (at the time, coaches were also sometimes referred to as “managers,” so research was a little blurred, but it does seem that he was at the time acting as a director). Specifically, he was involved in negotiations for the sale of the franchise to the NHL: a rival owner attempted to purchase the team, too, and arrived with ten $1,000 bills; another group from Ottawa was also bidding.

Hart’s instructions were: “Make sure you outbid the other people and get that club.” Hart called Leo Dandurand, the Habs’ owner, and convinced him to go to $11,000. No one could match that price. Sold.

Cece left in 1924 for the rival Maroons, but returned to serve as head coach in 1926-27, the first year the Habs played in the legendary Forum. Although the team had finished last place the season before he took over, Cece took them to two straight Stanley Cups in 1929-30 and 1930-31. Hart was “peppery” and “innovative,” and had his teams playing a fast, innovative, pressuring style. He never married, wedded instead to his businesses and to hockey. At times, he’d have five forwards on the ice, an unheard of strategy. These are the kinds of details I’m always searching for in books, but they’re few and far between.

Although he had led the Habs to the heights of the league, it wasn’t enough: D’Arcy Jenish wrote about the fickle and cantankerous fans and media questioning both Hart’s coaching decisions and whether “French Canada’s team should be coached by a French-Canadian, not an English-speaking Jew.” Cece left the team in 1932 (some debate about whether he resigned or was fired by Dandurand following a disagreement).

This observation’s something I’d love to be able to look into further, if I were smarter and had more time. The tension between all of these ideas. The Habs as an almost mythical bastion of French-Canadian identity. The fans’ distrust of Hart as an English-speaking Jewish man. The almost nationalistic fervor the team has inspired over the years. How hockey has been a way for outsiders to assimilate into Canadian culture itself. Cece’s own family history and ancestry, which included the literal scion of Canadian Jewry. Aaron came to Quebec around 1760 and Cece was fired, at least a little bit, for not being French-Canadian enough in the 1930s.

Either way, in 1936-37, after the Habs floundered without him, was asked to return. Hart stated that he would only do it if Howie Morenz returned, too. Morenz did, but later died due to complications from a hockey injury. The day after Morenz’s tragic death, the Habs were still scheduled to play a game. Hart said, “We were close. Real pals. I don’t know what to say, what to do or how we can hope to carry on tonight.” Despite this loss, Hart stayed on and continued coaching until 1939. When, depending on the source, he either retired due to illness or because the Habs’ new owner Ernest Savard fired him. Regardless of what actually happened, the illness led to his death in 1940.

Although the Habs would not win another Cup until 1944, they made the playoffs every season Cece was at the helm. His record with the Habs was 196-125-73, and in the playoffs, 16-17-4. After his death, the tributes were numerous. Lester Patrick, of the New York Rangers: “Cecil Hart was always a hard manager to beat, but a better sportsman I could not have found to lose to.” Bill Stewart, of the Chicago Black Hawks: “Loyalty to his team, fairness to an opponent, and willingness to abide by the letter of the rules, are characteristics I will always remember of Cecil Hart.”

To this date, I do not believe there has been another Jewish head coach in the NHL. Jeff Halpern, a former player and an assistant coach with the Tampa Bay Lightning, seems like our best hope for the next one. This idea—the dearth of them—was also something heavy on my mind when writing Eric’s character, and his own views about how his Judaism might be used by a team.

The first (goalies edition)

Joe Ironstone was the second Jewish player and the first Jewish goalie in the NHL, and he was very close to being the first—only ten days behind Sam Rothschild. Although he was born in Montreal, he grew up in Sudbury, another common thread between some of the early Jewish players.

He had what seemed like the 1924 equivalent of a PTO with the Ottawa Senators, but didn’t sign there. He went to the New York Americans in 1925, where he played one game where he allowed three goals against. In 1927, he was playing for the Toronto Ravinas, a minor league team, and was called up to the Leafs after their goalie was sick. The game ended in a 0-0 tie after a 10 minute overtime. The enterprising Joe asked for double the salary to play the next game. Conn Smythe agreed to the rate, but told him (accurately) that it would be the last game Ironstone ever played in the NHL.

He continued to play minor league professional hockey, and eventually retired in the 30s, returning to Sudbury to run the family business—Ironstone Men’s Wear—with his brother Moe.

Other early players

For an armchair researcher, it’s sometimes difficult to sort out what’s actually accurate and what’s not. For example, Sam Rothschild is generally accepted as the first Jewish player. But there are other, tenuous mentions. See, for example, Charlie Cotch, born in Libau in what is now Latvia, who played games for the Hamilton Tigers and the Toronto St. Pats in the 1923-24 (?) season (which, if he was Jewish, might make him the first player?).

Here, as you can see, the Journal stated that Cotch was “the only Hebrew player in the game,” but he is buried in a Christian cemetery (the Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Southfield, Michigan); this is the sort of Jewish connection that can be described (as it was by Irv Osterer in the Forward) as “tenuous at best.” One wonders whether the league at the time considered Eastern Europeans and Jewish players interchangeable.

Similarly, Wilfred Harold “Gizzy” Hart, who started in the NHL in the 1926-27 season with the Detroit Cougars, is credited in many places as the second Jewish player in the league.

Irv Osterer states, “Because of his famous hockey surname, many hockey aficionados erroneously concluded that Harold was a member of the tribe, but alas this is not the case.”

I haven’t been able to verify whether he was or wasn’t; a lot of what I looked at just refers back to encyclopedias, which do not list sources. I haven’t been able to actually view a primary source that confirms one way or another. Gizzy Hart was born in Saskatchewan in 1901, and while there was not a large Jewish population there, there were Jews in Saskatoon (for example, the Buller family moved in 1929 and the Jewish population was so small that they were able to make money boarding Jewish students at the University of Saskatchewan who wanted to reside in a kosher home). So while it’s possible that he could have been Jewish, it’s equally possible he wasn’t.

(There was another goalie, Maurice “Moe” Roberts, who began playing during this time and made appearances in NHL games in the 1920s and 1930s. His legendary contribution occurred in the 1950s, however, so we’ll discuss it there.)

The 1930s

In the 1930s, there are sometimes a few more crumbs of information about the players and their families. For example, there’s Alex “Mine Boy” Levinsky, a Syracuse-born defenseman who managed nine seasons in the NHL, split between the Leafs, the Hawks, and the Rangers. He got his nickname because his immigrant father used to yell, “That’s mine boy!” at games whenever Alex did something worth yelling about.

There’s something about that that’s just so charming to me. The knowledge that Jewish parents have been the same throughout history: just as proud and just as visibly Jewish.

The visibility is notable, particularly given the end of Alex’s career in Toronto: although he helped the Leafs win their first Cup as the Leafs (1932), Conn Smythe traded him to the Rangers. At least one fan was convinced that it was because of Smythe’s racism, claiming in the Toronto Star that he wouldn’t hire Jewish men to sell programs or refreshments at Leafs games, and supposedly trading Levinsky because of his religion. Given Smythe’s well-documented racism and treatment of Herb Carnegie (he is famously quoted as stating he would give anyone who could “turn Carnegie white” ten thousand dollars), this is also not hard to believe.

Nevertheless, Levinsky’s father was right to be proud of him; he played 367 NHL games and won two Stanley Cups before attending law school and becoming a lawyer and businessman.

Another player from the 1930s who definitely did not leave as much of an impact was Max Kaminsky.

Kaminsky was a center born in Niagra Falls, a 5’ 10”, 160 lb center. He played from 1933-37 for the Senators and the Bruins, and went into coaching after he retired, taking the St. Catherine Teepees to a Memorial Cup win in 1959-60. I do think, however, that it’s kind of cool how many Jewish players ended up working in hockey after retirement, either as coaching or trainers.

(Also, this isn’t the NHL, but it’s germane enough to mention and something I will always remember: Rudi Ball, a German winger who was initially denied a spot on the German national ice hockey team during the 1936 Winter Olympics. A friend and teammate refused to play unless Ball was included on the roster. As a result, Ball made a bargain with the Nazi government to save his family, so long as he played in the games. He was one of only two Jewish athletes representing Germany that year. There were reports that he was playing against his will and that he referred to his teammates as “they” rather than “we.”)

The 1940s

These were lean years for Jewish players, with only Hy Buller and Max Labovitch (a single season) representing in the major leagues.

Hyman “Hy” Buller was born in Montreal, as were many Jewish players of that time period, but after a tragic accident in the family’s cleaning business resulted in the death of Buller’s uncle, the family moved to Saskatchewan, where they had relatives. Hy grew up playing shinny in the streets and frozen ponds of Saskatoon, as well as numerous other sports. He fought frequently in the schoolyard as a result of antisemitic taunting. Still, as a natural athlete, Hy excelled at everything he did. However, he wasn’t allowed to join the best youth team in Saskatoon—the players were required to attend weekly church services. Hy, who attended Hebrew school and was bar mitzvah’d, was not eligible.

Nevertheless, scouts noticed him, and he received an invite to the New York Rangers’ training camp in Winnipeg. Because they were Jewish parents, Hy’s mother and father didn’t want him to go (he was a very good student, who’d graduated two years early, and they wanted him to focus on academia). Nevertheless, he began playing in the amateur leagues. Hy made his major league debut in 1944 with the Detroit Red Wings, but was sent down that season: he would remain in the minor leagues for eight years.

Hy, David Schwartz wrote, “with his mild, scholarly appearance, glasses and receding hairline, looked like someone who spent a lot of time in a library and knew from which end to read a book.” On the ice, however, he was a dyanmic skater, a clever stickhandler, and a hard-checking defenseman who was nicknamed “the Blueline Blaster” because he would hit other players in the space between the skate and their pads. And yet, he was also a family man: while playing for the Cleveland Barons, “the visiting Providence Reds were startled to see a determined Buller ram home a goal, skate into the net after it, and then come tearing to the Reds’ bench.” Hy wasn’t trying to fight: his wife had given birth to their son that night. The goal was a celebration, and his drive for the puck was to rescue the souvenier.

After doing his time in the minors, Hy held the record for most all-time sports scored by a defenseman in the AHL with 78 goals and 282 points. Although he was a technically a rookie heading into his first season with the New York Rangers, he was an experienced pro. That season, he was the runner up for the Calder trophy (losing to Boom Boom Geoffrion). And he racked up 96 PIM, despite the fact that some fans complained he wasn’t aggressive enough.

We return, to some extent, to Sam Rothschild’s signing and the Maroons’ hope that he would attract Jewish fans. The Rangers did the same, going so far as to hang banners with large Jewish stars from the rafters of Madison Square Garden. Hy indeed was popular and involved with the local community: he attended synagogue weekly with his family, refused to play on Yom Kippur, and always had time for the youths who sought his autograph.

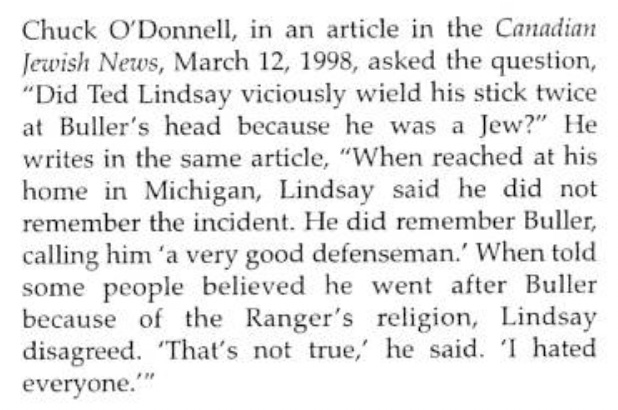

Not to say it was all puppies and rainbows. There was one incident in 1953-54 involving Ted Lindsay, who swung his stick twice at Hy’s head after a check. This almost comical passage follows:

Another stick-swinging incident followed involving Gus Morton of the Toronto Maple Leafs, but the violence of the modern game wasn’t what ended up forcing Hy’s retirement—he’d never been one to back down from a fight. What finally did it was a trade to the Habs in the 1954 offseason.

Hy announced his retirement before the 1954-55 season began. He didn’t want to uproot his family again, the salary was simply not enough to support them, and he was dealing with lingering injuries. The Buller family moved back to Cleveland, where he worked as a salesman. They then moved to Vancouver, where Hy, true to form both of himself and of many retired Jewish players, got into coaching amateur teams. He was diagnosed with cancer in 1965, and died in 1968, in his beloved Cleveland.

If you’re interested in more details about Hy’s life growing up in Saskatoon and playing in the professional leagues, I can’t recommend highly enough David Schwartz’s article A Mensch on Defense, the result of extensive research and interviews with Hy’s family and friends. It’s available in its entirety online.

The 1950s

The 50s were also pretty lean for Jewish players.

One of the most memorable moments involved Moe Roberts, who had been at one time one of the youngest professional goalies, but had long since retired from active play after joining the Navy during WWII. He found employment as an assistant trainer (or coach, depending on your source) with the Black Hawks. Apparently the Hawks didn’t have a back up goalie on the night of November 25, 1951, and when their starter was injured, Roberts had to step into the net. At the time the Hawks were playing the Bruins, led by the “Production Line” of Lindsay, Abel, and Howe. Roberts was unfazed, stating, “I’m ready. Just lemme see the puck.” He was 45 years and 345 days old, the oldest goalie to play an NHL game. I think he still holds that title. He was also the last NHL player who had been active in the 1920s to play a game.

Larry Zeidel, too, played a few games in the 50s for the Red Wings. He then spent many, many years in the minors. But the unfortunate incident for which he is most famous occurred in the 1960s during his last professional seasons, so we’ll mostly discuss him there.

The 1960s

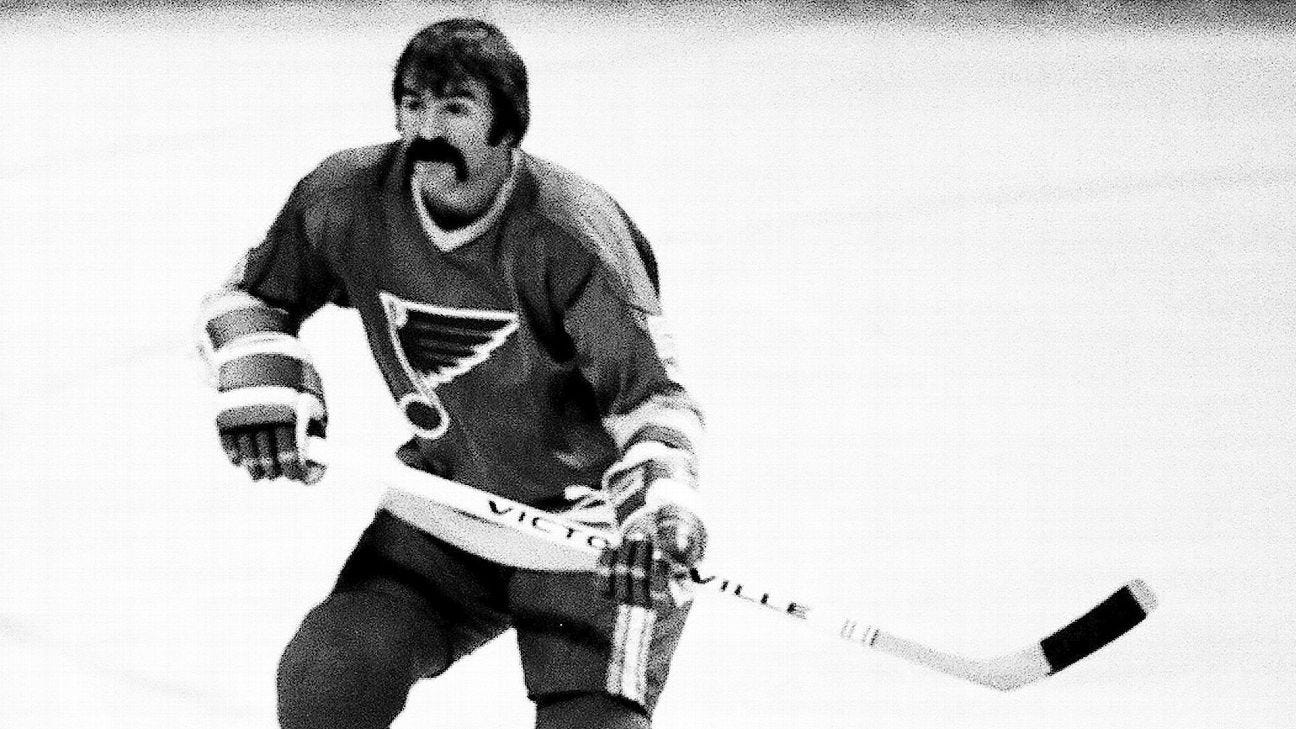

One of the first (and actually only) converts that I came across in my research was Bob Plager, who achieved 100 penalty minutes a season three times and was the originator of the quote, “You don’t have to be crazy to play hockey, but it helps.” He met his future wife, Robyn Sher, while he was a patient at what is now Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. He converted for her. He played eight seasons for the Blues, well into the 70s, before his retirement. He was briefly a head coach for the team, then, after he was let go, went into scouting. I think what sticks out to me about Plager is how generally tough it was to be Jewish in the NHL at this time, so a player choosing it, specifically for his spouse, is really notable.

One of the more tragic stories of the 1960s, and indeed this whole research, was that of Larry “the Rock” Zeidel.

Like many Jewish players, Larry was born in Montreal. His Romanian-Jewish grandparents had been cremated in a concentration camp during the Holocaust. As a child, he was subject to relentless antisemitic bullying, and developed a strategy of dealing with it: he would fight anyone who tried something. Eventually, they learned he wasn’t an easy target. After that, he started preemptively attacking the biggest bullies himself. These childhood patterns would continue during his professional career.

Larry played for several seasons in senior leagues (for those unfamiliar, this term doesn’t mean that the players were old, it means amateur or semi-professional hockey for adults), first in Quebec and then in Saskatoon, before starting his professional career with the Wings and the Hawks in the early 50s. In his first season—1951-52—the Wings won the Cup. He wasn’t long for the majors, however, and would spend many, many years toughing it out in the minors, where he developed a reputation as one of the most fearsome fighters in the entire league. He was frequently penalized, ejected, and in some cases, arrested.

The excerpt above describes one particularly nasty fight with Jack Evans of Saskatoon: the fans of that team would later taunt him with antisemitic slurs during games. Even Don Cherry, Larry’s defense partner on the Hershey Bears, stated that Larry never started anything with anyone who hadn’t deserved it or said something off-color to him or his teammates.

Larry would also fight rookie Eddie Shack (they would meet again in combat, notoriously, years later). This time, it was a stick fight which resulted in ten stitches for Larry. He would then go on to charge Shack in the stands, which led to a riot that drew in fans and law enforcement and criminal charges.

While many of Larry’s teammates would say that he was a kind man off of the ice, it would be difficult to say that this level of constant, destructive violence wasn’t terrifying. There was clearly something deeply broken about him, but he kept playing—and fighting—anyway, without a clear path to the majors. Just to give you an idea. In 1959-60, he had 293 PIM.

Finally, shortly before his 39th birthday, the NHL expanded with six new teams. Larry saw the opportunity: he had to do something. What he came up with was a brochure, complete with photographs of himself in hockey equipment and a business suit, which he sent to the expansion teams. This was accompanied by text: “I can help your organization in the front office with my experience in ticket sales and public relations as well as on the ice.” It is hard to square the image of Larry, with his bloody face and broken stick, with the ability to provide any assistance in public relations. But the brochure worked. The Philadelphia Flyers took a flyer on him.

Larry was just eager to play in the majors again, eager to belong. He was quoted as saying, “All I have to do is see this carpeting in the locker room and I’m motivated. We never had carpeting in the minors.” Something about that small detail really just kind of broke my heart, as well as the fact that he became a mentor and protector to both Joe Watson and Bernie Parent, his roommate on the road.

It didn’t get any easier for Larry, even though he’d finally made it back to the NHL.

Unfortunately, what Larry’s most remembered for, besides generally being a terrifying guy to play against, is the infamous stick fight with Shack. It happened at a Flyers home game in Toronto (already unusual: the roof had blown off the Spectrum, and it was still undergoing repairs, so the team had been temporarily relocated). The Flyers had been on a losing streak. And Larry, a man who’d been an enforcer his entire career, knew what he had to do. He later said, “I looked at the mood, I see the team is down. I figure I’m going to turn it up to high. I didn’t need an excuse, I’d had a thing going with Eddie Shack for a long time. The last time we were in Boston, the two of us had bumped during the warmup. I figured it was time to balance the books. So I went to the game like a kamikaze.”

The aggression started in the beginning of the game, with a cross-check and insults. Then, later on in the first period, Larry swung his stick at Shack’s head, opening up a gash. Shack hit back with his own stick and tore a gash of his own. Joe Watson later recalled that by the end of it, the players’ sticks were “down to twigs.”

According to Larry, the extreme violence of the fight was because Shack had been taunting him with antisemitic remarks. In his own words: “Nearly the whole Boston team tried to intimidate me about being the only Jewish player in the league. They said they wouldn’t be satisfied until they put me in a gas chamber. Boston started pulling this kind of stuff when we played them earlier in the season. I didn’t let it get to me even though it hurt me to hear it. It was bad on my part to try and ignore it then, because things only got worse and they really got bad just before the start of our last game in Boston Garden. That bit about me being a ‘Jew boy’ is music to my ears, but when they brought up the business of the gas chamber and extermination, well, I didn’t buy it.”

Whatever the genesis, the fight itself was absolutely brutal and left both men bleeding and in need of multiple stitches.

Watson recalled that even after the fight, Larry was still furious and ready to go. He was being sutured by the team’s doctors and found out that Shack was being treated in an adjacent room. “He took off, the needles still in his head and all. Doctors chasing him, cops restraining him.” The result: Larry was suspended for four games and Shack was suspended for three; both were fined $300.

Whether or not Shack actually said those things is a subject of debate to this day. Larry was insistent and repeated the claims to several reporters and authors. Shack denied it and so did his teammates. Clarence Campbell (at the time, the president of the league), after an investigation, backed him up. Even Ed Snider, the Flyers’ owner (and Jewish), stated that he was satisfied that the taunting as Larry described it had not occurred. At least two fans attending the game did corroborate Larry’s claims, at least to the extent that they had heard a Boston player shout obscenities referencing Larry’s religion. One of those witnesses named the Boston player in his statement, though the specific obscenity and the name was not published in the paper.

What is not up for debate is that after the incident, Bruins players continued to taunt him with antisemitic comments for the rest of the season, including with concentration camp references. (In a later article, Gerald Eskenazi stated that Larry had said the player who said, “You’re next for the gas ovens, Zeidel” wasn’t Shack.)

I don’t really have a conclusion to draw about this. Whatever happened, it happened, and Larry remembered it the way he remembered it. One of the uglier incidents in the game, the kind of aggression and slurs that we see echoes of today, even if not to this extent. And also, to some extent, the kind of rage that I think all of us have felt dealing with taunts and slurs, whether you were believed or not. (Some incidents in Eric’s past, too, reflect Larry’s experiences.)

Larry only played nine games in his second season with the Flyers, and that was it for his hockey career, at the age of 40. That’s a pretty impressive age for anyone to play until, let alone anyone who’d played as hard as Larry did.

After hockey, Larry found a second career as a marketing consultant, but he would be troubled throughout the years by complications from what would be diagnosed after his death as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). He became estranged from his wife and went through periods of homelessness, despite the fact that he was still beloved by family and friends and fans. If you’re reading this, you’re probably already familiar with CTE and its symptoms: personality changes, aggression and temper, impulsivity, headaches, dementia, and eventually, death. All of these things were present in Larry’s decline. The study of his brain was especially sobering. Doctors estimated that, based upon the severity of the damage, he had probably suffered more than a hundred concussions, losing consciousness over ten times.

Again…I don’t have a lot of conclusions to draw from this. Just a sad, tragic story. The darker side of hockey, always present at the edges.

He is buried in Baron de Hirsch cemetery in Montreal (coincidentally, where Eric’s father is buried and which is depicted in Home Ice Advantage).

The 1970s

Strangely enough, most of the Jewish players active in the ‘70s were goalies. There was Ross Brooks (maybe—like some of the earlier players, his Judaism appears to be up for debate), a longtime professional goaltender who nevertheless was one of the oldest rookies to break into the NHL, at age 36, later quoted as saying, “I came up the hard way. I never did anything special. The only thing I can always say is, ‘I was there.’ They can’t take that away from me.”

There was Mike Veisor, who played in Chicago and had wanted to be the first Jewish goaltender (apparently, no one remembers Joe Ironstone or Moe Roberts…) and was described as “[o]ne of the most agile goaltenders around; plays goal like a trapeze artist.” Unfortunately for Veisor, he was Tony Esposito’s backup, so the glory and the starts that might’ve been his went elsewhere.

And then there was Bernie Wolfe, born (shocker) in Montreal and undrafted. He played goal four seasons for the Washington Capitals before retiring at age 27 because he “just didn’t enjoy it anymore.” The main reason I want to talk about Bernie is his family, because this is just so universal to the Jewish experience and to my own writing of Jewish characters.

I cannot recommend highly enough this article by Leonard Shapiro. In just a thousand words he captured so much about the modern Jewish diaspora experience: the proud parents, the devotion to your family, the divide between your parents’ expectations and your dreams, even the desire to be seen not as Jewish but just as a professional in your field. In this article are some of my favorite Jewish mother quotes of all time.

I’ve never actually listened to her speak, but I can almost hear Fay Wolfe saying, “He’s such a good boy. You know, Butch calls three, sometimes four times a week.” And then there’s Shapiro’s observation that Fay would rather discuss Bernie’s less public achievments: his degree in finance, his marriage, and the fact that he had recently given her a granddaugther. The article actually gets even better with what might be the peak Jewish mother quote ever: “Of course I would have preferred him to be a doctor, or some kind of professional man. But if Bernie is happy, then we’re happy.”

(I found this article after writing the character of Eric, a Jewish boy from Montreal who calls his elderly mother every morning, a mother who is desperate for him to get married and ideally provide her with grandchildren. Quite literally, some things are just so universal.)

Even more interesting to me is Bernie himself, in the article, being asked about how it feels to be the only Jewish player in the NHL. Bernie immediately shut it down: “I don’t consider myself a Jewish hockey player. I consider myself a hockey player in the NHL.” Where a lot of the older players embraced and were proud of their identity, this is a departure from the norm—even though it wasn’t entirely accurate, since Wolfe and Veisor overlapped by a few seasons. I wonder whether the Zeidel incident wasn’t still fresh in their minds only a few years later. Whether some of that distancing might be a result of not wanting to make waves or make a stir. This, too, feels familiar to a certain part of my own youth.

The Shapiro article really resonated, apparently not just with me, but with other fans. In The Goaltenders’ Union, Bernie is quoted as saying that fans still bring it up: “She was such a typical Jewish mother. She was disappointed I wasn’t a lawyer or a doctor. I still get people coming up to me saying, ‘That was the greatest article I’ve ever read,’ because they were able to identify with it—not being a pro athlete but just with their own mothers.” And it’s true.

After his retirement, Bernie wrote a book called How to Watch Hockey (a very basic guide, geared towards new fans) and went on to found a successful financial planning firm.

One last amusing anecdote about Bernie. In 1992, the Caps tried to re-sign him (then 40 years old) so that they could expose him in the expansion draft and wouldn’t lose one of their regular goaltenders. Bernie agreed to sign for the league minimum and donate his salary to charity. However, the league said absolutely not. Phil Esposito, then the owner of the Tampa Bay Lightning, was quoted as saying, “I didn’t just pay $50 million [for this franchise] for Bernie Wolfe. He wasn’t any good when I played against him.”

The conclusion?

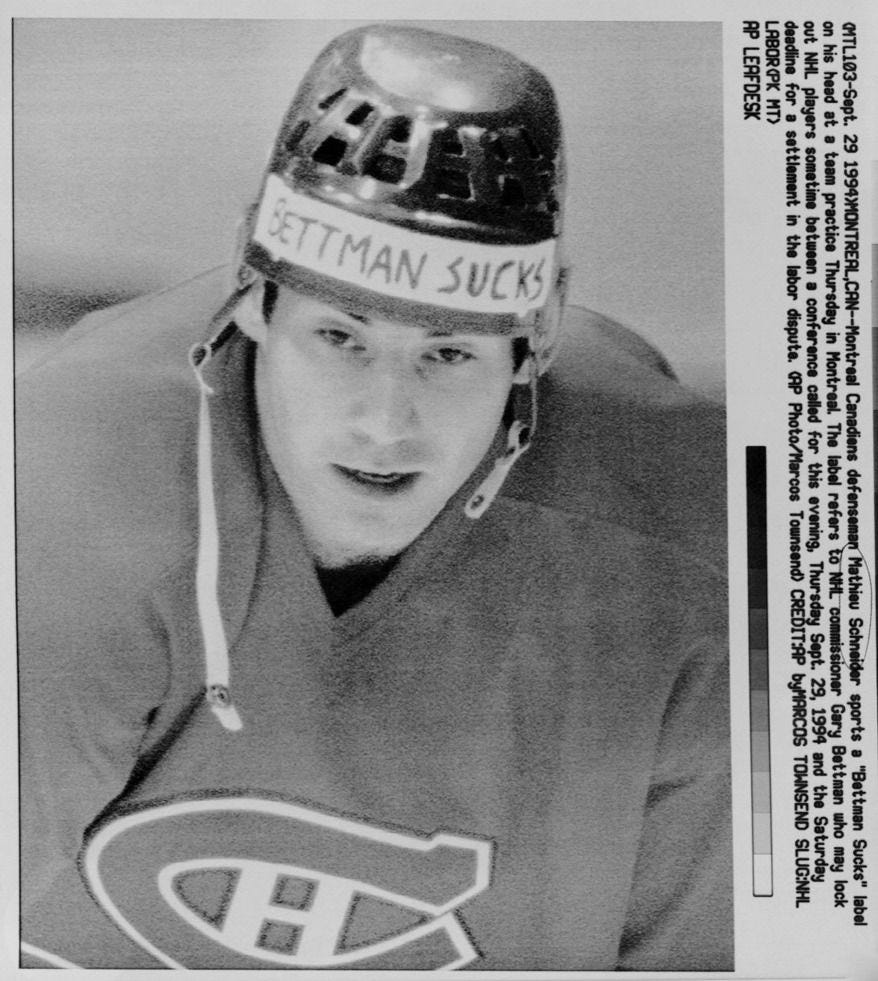

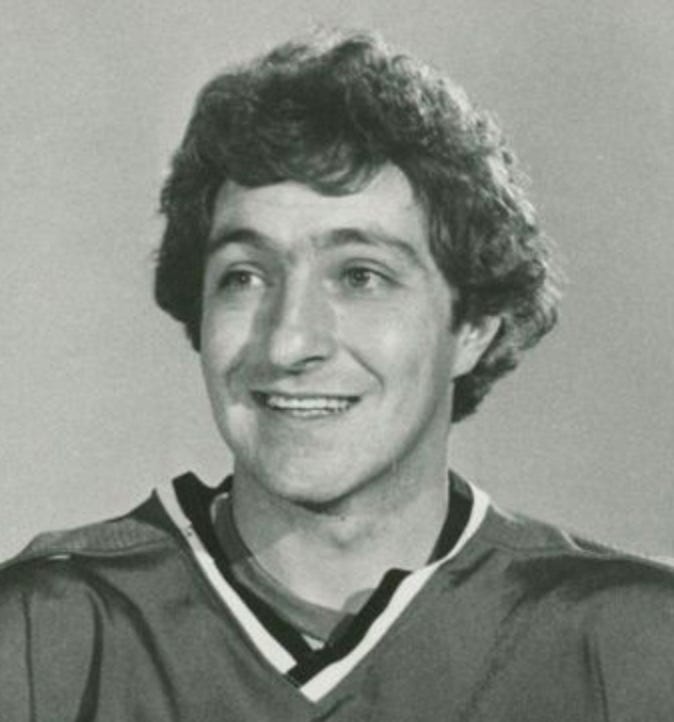

There are Jewish players who were active throughout the 80s and 90s, but I’m going to stop with the 70s because it’s the last decade that really feels historical to me at this point. Although I would be remiss not to post this picture of Mathieu Schneider, an undersized defenseman and one of the only Jewish players I had to follow in my youth:

(He was right for this, by the way.)

Or this quote in Great Jews in Sports, about an incident in which a member of the Buffalo Sabres insulted Mathieu on the ice, including the use of the word “Jew” in a “pejorative” tone: “That was the first time I heard any of that stuff. I made a mental note that the next time I had a chance, I would run the guy into the sideboards. And I did.” (Again: shades of Eric, in ways that will become evident in the book itself.)

After all of this reading and research I don’t really have much of a conclusion to offer except this: we’ve always been here.

We’ve been skill players and grinders and enforcers. We’ve been goalies and wingers and centers and defensemen. We’ve had our names on the Cup as early as the 1920s. Jewish players and coaches have had to deal with either being tokenized and used to draw in fans, or subject to antisemitic abuse, reviled and run out of town. Throughout the years, our parents have been there with us, as recognizable in the 1920s as they are in the 2020s. That, especially, is something that I have loved reading and discovering. Mr. Levinsky and Fay Wolfe, you will always be legends.

We’ve always been here, and we will continue to be. Reading these stories, and researching these men, I feel such a proprietary kinship. The same feeling that probably drove my own parents to point them out to me when I was younger. The same feeling that drove Alex Levinsky’s father to exclaim in pride:

That’s mine boy.

That sympathetic resonance. It’s there and it’s real. And it’s been so personally satisfying, to me, to work threads of these feelings, and these experiences, into my own books, whether on purpose or simply by accident of the universal Jewish experience.

Selected Sources

Adler, C. and Szold, H. 1936. American Jewish year book. Volume 38, American Jewish Committee.

Allen, Scott. “The Time the Caps Signed a 40-Year-Old Financial Planner to Circumvent NHL Rules.” Washington Post, 27 Nov. 2021, www.washingtonpost.com/news/dc-sports-bog/wp/2017/06/20/the-time-the-caps-signed-a-40-year-old-financial-planner-to-circumvent-nhl-rules/. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

Archive.org, 2023, web.archive.org/web/20160304060027/www.jewsinsports.org/profile.asp?sport=hockey&ID=3. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Archive.org, 2023, web.archive.org/web/20160303171917/jewsinsports.org/profile.asp?sport=hockey&ID=30. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Archive.org, 2019, web.archive.org/web/20190108035658/www.jewsinsports.org/profile.asp?sport=hockey&ID=27. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Cecil Hart - Bio, Pictures, Stats and More | Historical Website of the Montreal Canadiens.” Web.archive.org, 9 Sept. 2017, web.archive.org/web/20170909091830/ourhistory.canadiens.com/gm/Cecil-Hart. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Davis, Jefferson, and Andrew Podnieks. The Three Stars and Other Selections. ECW Press, 2000.

Diamond, Dan, and Ralph Dinger. Total Hockey. Kansas City, MI: Andrews McMeel; Toronto: Distributed in Canada by Canadian Manda Group, 1998.

Divver, Mark. “Mark Divver: A Hand from Milt Schmidt Helped Ross Brooks Make It with the Bruins.” Cape Cod Times, www.capecodtimes.com/story/sports/2017/01/12/mark-divver-hand-from-milt-schmidt-helped-ross-brooks-make-it-with-bruins/22701195007/. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

“Dwayne Roloson – at 45 Years of Age – Makes a Surprise Return to an NHL Team | the Hockey News.” Web.archive.org, 4 Mar. 2016, web.archive.org/web/20160304031426/www.thehockeynews.com/blog/dwayne-roloson-at-45-years-of-age-makes-a-surprise-return-to-an-nhl-team/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Eskenzai, Gerald. “They’ve Been Good Sports.” The Forward, 30 Mar. 2007, forward.com/opinion/10404/they-ve-been-good-sports/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Flyers Mourn the Loss of Larry Zeidel | NHL.com.” Web.archive.org, 4 Sept. 2023, web.archive.org/web/20230904192103/www.nhl.com/flyers/news/flyers-mourn-the-loss-of-larry-zeidel/c-722924. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Heritage Museums.” Sudburymuseums.ca, 2023, www.sudburymuseums.ca/index.cfm?app=w_vmuseum&lang=en&currID=1646&parID=1595. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

“HOCKEY’S OLD SCARS, NEW SLURS.” Web.archive.org, 4 Sept. 2023, web.archive.org/web/20230904192108/www.nydailynews.com/archives/sports/hockey-old-scars-new-slurs-article-1.773904. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

“How Conn Smythe’s Racism Kept Herb Carnegie from Achieving His NHL Dream.” Yahoo Sports, 29 June 2022, ca.sports.yahoo.com/news/how-conn-smythes-racism-kept-herb-carnegie-from-achieving-his-nhl-dream-185826604.html?guccounter=1. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Jenish, D’Arcy. The Montreal Canadiens: 100 Years of Glory. Toronto, Anchor Canada, 2009.

“Joe Ironstone.” Ice Hockey Wiki, icehockey.fandom.com/wiki/Joe_Ironstone. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Larry Zeidel at Eliteprospects.com.” Www.eliteprospects.com, www.eliteprospects.com/player/84527/larry-zeidel. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Larry “the Rock” Zeidel (1928-2014) - Find A...” Www.findagrave.com, www.findagrave.com/memorial/131499517/larry-zeidel. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

“Maurice Roberts 1942 Cleveland Barons | HockeyGods.” Hockeygods.com, hockeygods.com/images/15468-Maurice_Roberts_1942_Cleveland_Barons. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Meet the Most VIOLENT Player in Hockey History.” www.youtube.com, www.youtube.com/watch?v=hBtgZUyZFts.

“Moe Roberts’ Unlikely Path Made Oldest Goalie in NHL History | NHL.com.” www.nhl.com, 22 Nov. 2023, www.nhl.com/news/moe-roberts-unlikely-path-made-oldest-goalie-in-nhl-history. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Motchan, Bill. “Jews and the St. Louis Blues: 7 Things You Might Not Know.” St. Louis Jewish Light, 6 June 2019, stljewishlight.org/arts-entertainment/jews-and-the-st-louis-blues-7-things-you-might-not-know/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Oliver, Greg, and Richard Kamchen. Goaltenders’ Union, The. ECW Press, 2014.

“Ontario Jewish Communities | Sudbury - Sports.” Web.archive.org, 5 Apr. 2023, web.archive.org/web/20230405201947/www.ontariojewisharchives.org/exhibits/osjc/communities/sudbury/community/sports.html. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Osterer, Irv. “Meet Every Jewish Name That Has Ever Been Inscribed on NHL’s Stanley Cup.” The Forward, 22 June 2022, forward.com/culture/506996/nhl-stanley-cup-jewish-players-sammy-rothschild-hockey/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Postal, Bernard, et al. Encyclopedia of Jews in Sports. New York, Bloch, 1965.

puckstruck. “Hart Beat.” Puckstruck, 28 Nov. 2020, puckstruck.com/2020/11/28/hart-beat/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Rothschild, Samuel “Sam” – CCA Hall of Fame | ACC Temple de La Renommée Virtuelle. www.curling.ca/hof/people/rothchild-samuel-sam/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

“Rudi Ball: The Jewish Ice Hockey Star Who Represented and Survived Nazi Germany.” BBC Sport, 7 June 2023, www.bbc.com/sport/ice-hockey/65821199. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

“Sam Rothschild Stats, Height, Weight, Position, Salary, Title.” Hockey-Reference.com, www.hockey-reference.com/players/r/rothssa01.html. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Schwartz, David A. “A Mensch on Defense: The Hy Buller Story.” The Scribe 22, no. 1 (2002): 8-32.

Shapiro, Leonard. “My Son, the Goalie.” Washington Post, 9 Feb. 1977, www.washingtonpost.com/archive/sports/1977/02/09/my-son-the-goalie/97c7c7fb-3d20-43ff-bbce-364c11e2af34/. Accessed 9 Dec. 2023.

Siegman, Joseph, and Mark Spitz. Jewish Sports Legends: The International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. Lincoln, University Of Nebraska Press, 2020.

Slater, Robert. Great Jews in Sports. Middle Village, N.Y., Jonathan David Publishers, 2010.

“This Day in Hockey History – March 7, 1968 – Zeidel and Shack Slur-Fueled Stick Swinging?” The Pink Puck, 7 Mar. 2019, thepinkpuck.com/2019/03/07/this-day-in-hockey-history-march-7-1968-zeidel-and-shack-slur-fueled-stick-swinging/. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

Wechsler, Bob. Day by Day in Jewish Sports History. KTAV Pub. House; New York, 2008.

Wikipedia Contributors. “1924–25 Montreal Maroons Season.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Aug. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1924%E2%80%9325_Montreal_Maroons_season. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Wikipedia Contributors. “1925–26 Montreal Maroons Season.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 27 Aug. 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1925%E2%80%9326_Montreal_Maroons_season. Accessed 8 Dec. 2023.

Wolfe, Bernie, and Mitch Henkin. How to Watch Ice Hockey. Bethesda, Md.: National Press; Scarborough, Ont.: Prentice-Hall Canada, 1985.

Wong, John Chi-Kit. Lords of the Rinks: The Emergence of the National Hockey League, 1875-1936. Toronto; Buffalo, University of Toronto Press, 2005.

Zweig, Eric. The Big Book of Hockey for Kids. Scholastic Canada, 1963.