show your work

a discussion of some of my background reading for game misconduct

Introduction

I’ve always loved hockey.

My mom grew up going to Flyers games in the 70s, back when they were the Broad Street Bullies and back when they were actually winning Cups. At that age, it was an uncomplicated love. Hockey is a beautiful, exciting sport to watch, and I experienced the excitement of the Eric Lindros draft drama and the heartache of losing in the finals to the…Red Wings.

It was such a huge part of my life, both family and otherwise, growing up, that it was honestly an extremely rude and depressing wakeup call to realize that it wasn’t a sport that would ever love someone like me back, not in any concrete and meaningful way. Because I’m a stubborn little asshole, I wasn’t willing to give it up. But I did want to understand.

So I started reading. And reading. And reading.

And you know what? It’s the beautiful game, but hockey’s pretty fucked up. Like, from its basest level, the sport is incredibly fucked up, from the time that teenagers are sent away from their families to live in billets and paid stipends to play a sport, to guys who should have retired years ago pushing their bodies through the last few seasons because they don’t know how to do anything else, to marginalized players dealing with abuse from their own goddamn teammates, the guys who should have their backs.

There is a lot of information out there, especially now, both academic papers and books and documentaries. The Players’ Tribune gives the players a more direct voice to talk about their experiences and feelings. The more I read the more the authorial part of my brain started roaring into life. There’s just so much to fucking say about this stupid sport and all of its stupid problems that only a few people on the margins seem interested in trying to fix at all.

As a sports fan, it’s depressing.

As an author, boy howdy did I have a lot to say about that.

And that was the genesis of Game Misconduct (and to varying degrees, the rest of what I’ve been calling the Penalty Box series).

Generally

Is it a little pretentious to say that your gay romance novel is about toxic masculinity in hockey? Maybe, but there’s so much to say about it. Because it permeates everything about this sport. It’s inextricable from the sport itself.

From the earliest time these guys get onto the ice as elementary school students, they are subjected to a homogenous, all-consuming culture that does its level best to reinforce that you have to be a tough guy, that you don’t complain about being hurt, that you do everything for the team, that pushes out anyone who doesn’t fit in. Smarter people than I have written the academic papers but it’s all there if you’re writing a book (if you’re interested my full bibliography can be found here).

To give you a little example of some of the kinds of things I was considering, here’s a screenshot from the table of contents of Kristi Allain’s 2012 PhD thesis:

In the real world, the NHL is a league where, although statistically there have to have been many queer players playing since it was formed in 1917, no one actively playing for an NHL team has come out. There’s a whole (excellent) documentary talking about why that is—it’s hard. The casual homophobia in locker rooms that you hear from the earliest years is so goddamn tough to deal with. A lot of guys stop playing instead of pushing through. A lot of guys would rather stay in the closet than rock the boat. With the recent and unfortunate backsliding trend of teams not wearing pride jerseys on pride nights, you can see why.

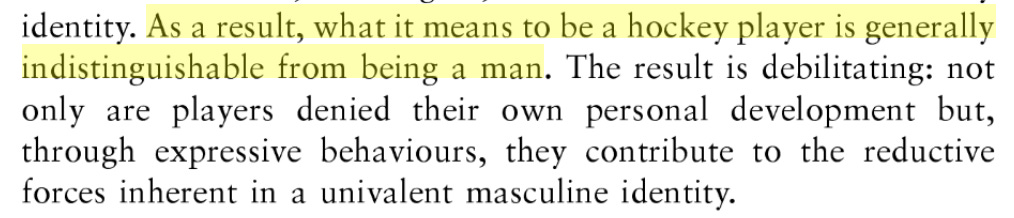

But it’s not just closeted players who deal with the consequences. It’s all of them. The very specific way that hockey players are socialized, the glorification of pushing through horrific injuries and being “hockey tough”—all of this is a result of the hypermasculine identity that’s inextricably tied into the sport and its culture.

Overall, in my books, the goal was to present a more diverse league, to show what that could look like and what that might mean for the characters playing in it. But even in my fictional world, it is still pretty heavily based in reality, and they are still dealing with the culture of the sport and the consequences that would have on personal development at a very impressionable age.

This quote from Michael Robidoux’s absolutely fantastic Men at Play is one I think of frequently when writing:

Danny

Danny is an archetype that is headed out of the league. A hell of a lot of ink has been spilled about enforcers and their place in the game and whether fighting has a place in hockey and exactly why enforcers were needed in the first place. Almost anyone will tell you that enforcers were needed to protect the stars, to police the game because the players couldn’t trust the league to do it for them (also, on this note, you might be interested in reading Ross Bernstein’s The Code, which discusses the unwritten rules that govern NHL fighting).

There’s a lot to say about the Department of Player Safety and their continued failure to do that in any meaningful way, but the fact of the matter is, the game has evolved so much that there simply isn’t space for guys who are only there to hit people. And yet, there are still the Ryan Reaves and Nic Deslauriers of the league. They can play limited roles, but you know why they’re there. And that was the genesis of Danny’s position with the Hornets: he’s there to protect the stars.

If you’re interested in learning more about enforcers, the documentary Ice Guardians is available for free streaming here. I’m a little hesitant about recommending it because it is definitely a bit more nostalgic about the roles than I would hope that players should actually be, but there are so many personal accounts and details that were invaluable to me writing this book that I do have to mention it.

For more unvarnished looks at the cost of fighting, a lot of ink has been spilled on the topic. There’s Jeremy Allingham’s Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey, for example, but you can also turn to personal accounts. Daniel Carcillo has talked at length about his post-concussion symptoms and has lead several class action lawsuits of former players against the league. Marc Savard has written an article about how difficult it was for him to deal with the consequences of one horrific injury.

But I found myself returning most often to Nick Boynton’s chilling article “Everything’s Not Okay,” where he talks at length about the damage he did to himself playing hockey, about the 20-30 concussions he probably suffered on top of the 8 or so officially diagnosed head injuries. He talks about the later stages of his career, about getting hit and not remembering what would happen afterward. He’d still be playing, but it was like watching someone else in his body on TV later. The quote that really stuck with me when I was thinking about Danny’s character and the way he would act was:

But by that point, I honestly didn’t even care anymore. I was gone, man. Straight up. I didn’t feel anything. I was a dead man skating. My last few seasons, I was out there basically just flat-out killing myself for a paycheck.

That’s Danny; that’s who he is in a nutshell. A dead man skating.

And why?

Why would you essentially kill yourself for a sport?

It all goes back to hockey culture. The glorification of pushing through injuries to keep playing. And the lack of knowing what to do after you stop playing (back again to Robidoux). So many of these guys have so much tied up in their identities as hockey players that even the idea of having to retire is terrifying. And even beyond that, some of them are just willing to do anything to keep playing in pursuit of a Cup. Look at recent examples just on one team—Shea Weber, Carey Price, and Paul Byron all pushed through serious injuries to keep playing through the Habs’ Stanley Cup run in 2021, and all of them are essentially medically retired due to the consequences of the stress and trauma that they put on their bodies during that time.

On that same topic from a slightly different angle, TSN recently released an excellent documentary about the problems with painkiller use in the NHL—and this isn’t just opioids, but NSAIDs. Essentially, players are regularly taking huge and dangerous amounts of drugs that are meant to be used in smaller doses and for shorter amounts of time, and paying the physical costs (Ryan Kesler was later diagnosed with colitis, which was exacerbated by Toradol overuse), simply so they can get back out on the ice faster. It’s not just the teams pushing painkillers at them, but sleeping pills, anti-anxiety medication—pretty much anything a player wants access to, he’s got access to, and in dangerous quantities.

And there’s real life inspiration for guys like Danny who don’t get the happy endings, as well—unfortunately, the deaths of Derek Boogaard and Rick Rypien and Steve Montador, all of whom struggled with either substance use disorder or depression or both. All of them informed Danny’s background and history. There’s the excellent biography Boy on Ice about Boogaard’s life and death, if you’re interested in reading more. Corey Hirsch has also written at length about his struggles with OCD and depression, and Colin Wilson wrote first about his OCD and mental health issues, and then, a year later, about his substance use disorder.

Mike

There’s definitely a lot of overlap in the reading for Danny and Mike, because a lot of the same issues with regard to fighting apply to Mike as well. For Mike’s character, though, I did additional reading into the homogenity of CHL locker rooms because the hazing and rituals there absolutely shaped who he is as a person, and also because he’s younger and the scars are fresher. Mike left home as soon as he could, and was drafted into the in-world equivalent of the WHL. He moved hours and hours away from his home in Southern California to live with a billet family and play hockey in Portland.

But once he got there? Mike stuck out like a sore thumb as a player who wasn’t Canadian, wasn’t white, and wasn’t a giant. As a result, he had to both fit in as best he could, and be a tough guy when he couldn’t. I don’t go into a ton of detail about his time playing in juniors in this in the book, but it absolutely formed the way he reacts to other people and himself, and the way he went about his first sexual experiences. He’s so deeply in the closet and terrified of anyone finding out that in addition to all of the other ways he doesn’t fit in that he’s gay, he can barely even say the word to his best friend.

For this, Kristi Allain and Cheryl MacDonald’s work and interviews with CHL players were absolutely invaluable. Both women have written books on the topics, but their theses and papers are absolutely worth checking out as well. It’s a pretty grim picture of what it must be like spending all of your time with a team where you know exactly how different you are. When the whole locker room culture is so focused to a fault on fitting in, not rocking the boat, doing everything for the team, when anyone who doesn’t fit in isn’t just ostracized, but actively harrassed and bullied.

Mike is a product of all of that: the only emotion that he’s ever really allowed to experience is rage. And he doesn’t even fully have the words to express even that limited range of feeling.

Their character arcs

Mike and Danny are both fundamentally broken men who have dealt or failed to deal, in varying ways, with the trauma that playing hockey has wrought on their lives. Of living with and under this culture from very formative years and long into adulthood.

In that sense, their character arcs are both about, eventually, finding a way to heal and become better people.

Mike’s is learning to open up to other people, to allow himself to experience his own emotions in a real way for the first time in his life and express them in words, to let himself believe that he can be better than he is.

Danny’s is learning that he has value besides the damage he does to his own body, to allow himself to accept the help that people want to give him, to realize that despite his darkest thoughts about himself, people can and do actually love him and believe in him.

So what it comes down to when writing this book, everything that Danny and Mike think and feel and do—even the way they fuck—is a result of how they’ve been socialized, how they’ve had to adapt to survive in the league, the inherent violence that has always been such a huge and driving force in their lives. They’re not men who have ever really been allowed to show vulnerability. To admit to any weakness. It’s something they have to learn, and they only do end up learning that through each other. And it’s a long road for both of them.

I guess I should probably wrap this up by saying that whether I’ve actually accomplished any of this is up to your own opinion, but I hope that I’ve given you some food for thought and further reading. This is just the tiniest sliver of what’s out there if you know where to look and have the desire to do the research. There’s really so much to say about this sport, and so much work to be done to make it a safer, equitable, and more welcoming sport for everyone. But regardless, it has truly been a pleasure both writing and researching this book, and I hope you enjoy reading it just as much.

Selected Sources

Allain, Kristi A. “‘A Good Canadian Boy’: Crisis Masculinity, Canadian National Identity, and Nostalgic Longings in Don Cherry’s Coach’s Corner.” International Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 52, 2015, pp. 107–32. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.3138/ijcs.52.107.

Allain, Kristi A. “‘Real Fast and Tough’: The Construction of Canadian Hockey Masculinity.” Sociology of Sport Journal, vol. 25, no. 4, 2008, pp. 462–81. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.25.4.462.

Allain, Kristi A. “‘What Happens in the Room Stays in the Room’: Conducting Research with Young Men in the Canadian Hockey League.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, vol. 6, no. 2, 2013, pp. 205–19. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676x.2013.796486.

Allingham, Jeremy. Major Misconduct: The Human Cost of Fighting in Hockey. Arsenal Pulp Press, 2019.

Boynton, Nick. “Everything’s Not O.K.” The Players’ Tribune, 13 June 2018, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/nick-boynton-everythings-not-ok.

Branch, John. Boy on Ice: The Life and Death of Derek Boogaard. Reprint, W. W. Norton and Company, 2015.

Carcillo, Daniel. “Gone.” The Players’ Tribune, 22 Apr. 2015, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/nhl-daniel-carcillo-steve-montador-video.

Carcillo, Daniel. “I Can’t Live Like That Anymore.” The Players’ Tribune, 13 June 2018, www.theplayerstribune.com/videos/daniel-carcillo-head-trauma.

Carcillo, Daniel. “The Fourth Period.” The Players’ Tribune, 8 June 2016, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/daniel-carcillo-hockey-concussions-depression-steve-montador-2016-6-8.

Colburn, Kenneth, Jr. “Honor, Ritual and Violence in Ice Hockey.” Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, vol. 10, no. 2, 1985, p. 153. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.2307/3340350.

Dennie, Martine, and Paul Millar. “Exploring the Subcultural Norms of the Response to Violence in Hockey.” Sport in Society, vol. 22, no. 7, 2018, pp. 1297–314. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1529027.

Hirsch, Corey. “Dark, Dark, Dark, Dark, Dark, Dark by Corey Hirsch | The Players’ Tribune.” The Players’ Tribune, 16 Feb. 2017, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/corey-hirsch-dark-dark-dark.

Hirsch, Corey. “I’m Not Brave at All.” The Players’ Tribune, 28 Jan. 2021, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/corey-hirsch-nhl-hockey-mental-health.

Hirsch, Corey. “You Are Not Alone.” The Players’ Tribune, 25 June 2018, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/corey-hirsch-you-are-not-alone.

MacDonald, Cheryl, et al. Overcoming the Neutral Zone Trap: Hockey’s Agents of Change. University of Alberta Press, 2022.

MacDonald, Cheryl. “That’s Just What People Think of a Hockey Player, Right?”: Manifestations of Masculinity among Major Junior Ice Hockey Players. Masters Thesis, Concordia University, 2012.

MacDonald, Cheryl. “Yo! You Can’t Say That!”: Understandings of Gender and Sexuality and Attitudes Towards Homosexuality Among Male Major Midget AAA Ice Hockey Players in Canada. PhD thesis, Concordia University, 2016.

Robidoux, Michael. Men at Play: A Working Understanding of Professional Hockey. First, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001.

Savard, Marc. “Hell and Back.” The Players’ Tribune, 17 May. 2017, www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/marc-savard-bruins-hell-and-back.

Wilson, Colin. “Addiction by Colin Wilson.” The Players’ Tribune, 25 Oct. 2021, www.theplayerstribune.com/posts/colin-wilson-nhl-hockey-addiction.

Wilson, Colin. “The Things You Can’t See.” The Players’ Tribune, 23 Nov. 2020, www.theplayerstribune.com/posts/colin-wilson-nhl-hockey-mental-health.

I had an ARC of Game Misconduct and loved it (I've never watched a hockey game in my life, and that mattered not in the slightest) so I really appreciate these insights into your research and thinking.

Hi hi! I have yet to read your book, so some of the references to your own characters probably flew over my head, but i enjoyed this letter regardless. Or -- enjoyed is a strong word, but i don't know much about hockey at all, and i love learning more about it. I've already read some of the articles you linked, but i always love being reminded of their existence. The reality is chilling and frankly extremely upsetting, but i hope these articles and documentaries are only the first step, and that it means the culture is shifting. I realise it doesn't look that way now, but i can only hope. As for the characters, again, i haven't read your book yet, which i'll have to amend soon, but just the amount of research really makes me excited and anticipatory of the depth ill find in it. Sometimes i am extremely overcome with an unbridled empahty for men, and thinking about hockeys' inner lives really does that. This has turned into a very uncohesive comment, so as a closing thought, i want to say i really enjoy getting to see even just a little glimpse of the behind the scenes of building a book and building characters, so thank you for sharing!!